|

restoring our biblical and constitutional foundations

|

Karl Barth and the German Church Conflict

In my essay “Do We Need a New Barmen Declaration?” I attempted to discuss some of the disconcerting similarities between the Third Reich of Adolf Hitler and the current scene in America. The most disturbing parallels concern what appear to be the reluctance on the part of the Christian church in America to confront the evils of statism in a way the Confessing Church of Germany did in the 1930s.

This does not mean that the state is inherently anti-Christian or that it always fails to promulgate Christian convictions. In fact, political leaders and parties often claim to stake out their positions believing they are supporting biblical principles. The problem, however, is this: in the very act of asserting its “Christian” principles, the state all too easily undermines the very principles it purportedly seeks to sustain. The result, unfortunately, is a situation in which you have wolves that appear very much like sheep.

As

Christine Elizabeth King has shown in her book The Nazi State and the

New Religions, many Nazi party leaders used religious ideas freely in

their speeches, especially Goebbels and even Hitler, who declared himself

to be God’s

special agent. Moreover, biblical terminology can be found in

many party speeches, though because of its Jewishness the Old Testament

was taboo. References made in Nazi circles to “positive Christianity” show

an awareness of the ideas later adopted by the German Christians. These

references suggested that Jesus was a true Aryan who had founded “positive

Christianity,” which, however, had been corrupted by the “Rabbi” Paul who

judaized Christ’s heroic Aryan ideals. As King notes, “Pauline theology

had thus corrupted Christianity, but Hitler had arisen to cleanse it and

restore it in its true form to Germany.” Many Christians in Germany

believed this new emphasis accorded with attempts to make the church’s

teaching relevant and to “demythologize” the Old Testament and parts of

the New Testament in ways suggested by the liberal trends of the day.

As early as 1920, the program of the NSDAP stated its support for “positive Christianity,” which proved to be an invaluable tactical aid in convincing the religious masses that they could support National Socialism without betraying their religious convictions:

We insist upon freedom for all religious confessions in the state, providing they do not endanger its existence or offend the German race’s sense of decency and morality. The Party as such stands for a positive Christianity, without binding itself denominationally to a particular confession. It fights against the Jewish-materialistic spirit at home and abroad and believes that any lasting recovery of our people must be based on the “spiritual principle” that the welfare of the community comes before that of the individual.

Nazi propagandists encouraged such thinking although they presented the new emphasis in terms that linked it clearly to the new political message. Party rallies were made to appear as a form of “divine service” (Gottesdienst) or the equivalent. Similarly, the party had its own religious “texts” in the form of slogans. The Jews were the “enemy,” and the mention of “evil” became identified with traditional Christian anti-Semitism. Thus the “satanic influence” of Judaism had to be destroyed before the political millennenium was possible.

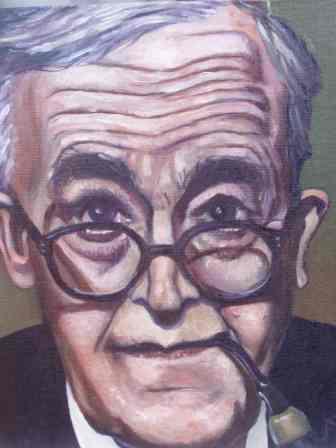

If the church struggle in Germany was a struggle for religious liberty under a totalitarian state, it was also—and perhaps primarily—a struggle of the church against itself—a struggle for it to remain faithful to the Gospel and to Jesus Christ. As I mentioned in my previous essay, it was Karl Barth, then professor of systematic theology in Bonn, who became the leading spokesman for a small but articulate group within the Protestant churches that challenged the ethos of National Socialism by an abrasive call to return to the prophetic witness of the biblical revelation. Above anything else, it was the ecclesiastical triumphalism of the Protestant establishment that provoked him to write his polemics against the state, including a piece entitled Quousque Tandem, a portion of which may be quoted here:

Laying aside all professional long-windedness, discretion, and prudence, I have this comment to make: It is a scandal which cries to heaven that the German evangelical church is always talking in this way…. Professor Schneider speaks for dozens of our leaders and for hundreds and thousands of our pastors. I have nothing against him and those like him, but I have everything against the sort of language with which he and the army of those like him are leading this country astray. I am sick, too, of holding my peace…. If we allow ourselves to be constantly addressed in this way, if we fail to protest, if this language is listened to and given credence, then in its inmost being the Church has already ceased to live.

Barth thus set himself against the establishment church of his day, and the dividing lines had been clearly drawn. Reich Bishop Ludwig Müller had proclaimed, “We must emphasize with all decisiveness that Christianity did not grow out of Judaism but developed in opposition to Judaism. When we speak of Christianity and Judaism today, the two in their most fundamental essence stand in glaring contrast to one another. There is no bond between them, rather the sharpest opposition.” Barth, however, made it clear that such a position on Judaism was unacceptable. In 1933 he wrote:

Protests against the German Christian heresy cannot simply begin with the Aryan Paragraph, nor with their rejection of the Old Testament, the Arianism of their Christology, the naturalism and pelagianism of their teachings of justification and sanctification, nor with the idolization of the state that characterizes German Christian ethics. Rather our protest must be directed fundamentally at the source of all those individual heresies: at the fact that, next to the holy scripture as the sole revelation of God, the German Christians claim German Volkstum, its past and its political present, as a second revelation. We thereby recognize them as believers in “another God.”

“Believers,” yes, said Barth; but “believers in

another God”! To Barth, the essence of the German Christian movement was

obvious. By elevating Volkstum—race—to the level of revelation,

they had opened the floodgates to a torrent of non-Christian and

anti-Christian beliefs, attitudes, and activities. Blurring racial and

religious categories, the German Christians defined the church as

essentially and primarily anti-Jewish, and it was this idea that became

the fixed point around which spokesmen of the movement structured and

organized their views.

“Believers,” yes, said Barth; but “believers in

another God”! To Barth, the essence of the German Christian movement was

obvious. By elevating Volkstum—race—to the level of revelation,

they had opened the floodgates to a torrent of non-Christian and

anti-Christian beliefs, attitudes, and activities. Blurring racial and

religious categories, the German Christians defined the church as

essentially and primarily anti-Jewish, and it was this idea that became

the fixed point around which spokesmen of the movement structured and

organized their views.

When Hitler became Chancellor on January 30, 1933, the German Christians were already well organized. Hiller’s policy at this time was still to try and persuade the populace that his party was Christian and that he himself was neutral with respect to the various denominations. Thus in his speech before the first meeting of the Reichstag on March 23, 1933, he declared:

The national Government sees in the two Christian Confessions the most important factors for the preservation of our nationality. It will respect the agreements that have been drawn up between them and the provincial states. Their rights are not to be infringed. It expects, however, and hopes that conversely the work upon the national and moral renewal of our nation, which the Government has assumed as its task, will receive the same appreciation. All other denominations will be treated with the same impartial justice…. The rights of the churches will not be curtailed; their position in relation to the State will not be changed.

When

the German Christians held their first national convention in Berlin on

April 3-5, Dr. Friedrich Werner, later president of the Evangelical Church

government office, declared that the basis of the church’s constitution

had to be the “Führer” principle. Only then could the unification of

church and state produce the necessary increase of power needed by the

nation. The convention closed by passing a resolution that called for the

creation of a Reich Church and the right

of believers to revolt. The

resolution included these words:

God has created me a German. Germanism is a gift of God. God wants me to fight for my Germany. Military service is in no sense a violation of Christian conscience, but is obedience to God…. For a German the Church is the fellowship of believers who are obligated to fight for a Christian Germany. The goal of the “Faith Movement of ‘German Christians’” is an evangelical German Reich.

With this statement we come to the relevance of this essay to our own situation. Barth and others like him resisted peace at any price. To those who believed in accommodation with the idolatrous state he stated, in unmistakably clear terms, “No Compromise!” Thus the heart of the German church struggle lay in the confessing of Jesus Christ, for to confess Christ meant not to confess others as Christ. Witness to Jesus Christ alone meant, under the Third Reich, the denial of neo-German paganism and of the German-Christian heresy. Certainly we are in a totally different situation today, yet as we read these statements of Barth we find our own situation mirrored in them. It may be that our way forward is also to be found in them—the way of confession to Jesus Christ alone.

July 17, 2003

David Alan Black is the editor of www.daveblackonline.com.